As most readers probably know, Ben Bernanke has developed and promoted the thesis that the crisis was the result of a “global savings glut,” which is shorthand for the Chinese are to blame for the US and other countries going on a primarily housing debt party. This theory has the convenient effect of exonerating the Fed. It has more than a few wee defects. As we noted in ECONNED:

The average global savings rate over the last 24 years has been 23%. It rose in 2004 to 24.9%. and fell to 23% the following year. It seems a bit of a stretch to call a one-year blip a “global savings glut,” but that view has a following. Similarly, if you look at the level of global savings and try deduce from it the level of worldwide securities issuance in 2006, the two are difficult to reconcile, again suggesting that the explanation does not lie in the level of savings per se, but in changes within securities markets.

Similarly, the global savings glut thesis cannot explain why banks created synthetic and hybrid CDOs (composed entirely or largely of credit default swaps, which means the AAA investors did not lay out cash for their position) which as we explained at some length, were the reason that supposedly dispersed risks in fact wound up concentrated in highly leveraged financial firms.

By contrast, the Borio/Disyatat paper tidily dispatches the savings glut story, and develops a more persuasive argument, that the crisis was due to what they call excess financial elasticity, which means it was way too able to accommodate bubbles. From Andrew Dittmer’s translation of the paper from economese to English:

The idea of “national savings” or “current account surplus” refers to the total amount of exports sold minus the total amount of imports sold (more or less). The “excess savings” theory holds that this excess had to have been financed somehow, and so presumably by countries in surplus, like China.

However, for the US in 2010, the total amount of financial flows into the US was at least 60 times the current account deficit (9), counting only securities transactions. If this number were correct, then inflows would be 61 times the current account deficit, and outflows would be 60 times the current account deficit. The current account deficit is a drop in the bucket. Why would anyone assume it had anything to do with the picture at all?

Moreover, if the “savings glut” theory was correct, we would expect there to be certain historical correlations between the following variables: (a) current account deficits of the US, (b) US and world long-term interest rates, (c) value of the US dollar, (d) the global savings rate, (e) world GDP. There aren’t (4-6, see graphs).

You would also expect credit crises to occur mainly in countries with current account deficits. They don’t (6).

Suppose we look at a more reasonable variables: gross capital flows (13-14). What do we learn about the causes of the crisis?

Financial flows exploded from 1998 to 2007, expanding by a factor of four RELATIVE to world GDP (13), and then fell by 75% in 2008 (15). The most important source of financial flows was Europe, dwarfing the contributions of Asia and the Middle East (15). The bulk of inflows originated in the private sector (15).

If we look instead at foreign holdings of US securities (15-16), Europe is still dominant, but China and Japan are a little more prominent due to their large accumulations of foreign exchange reserves (15). Still, the Caribbean financial centers alone account for roughly the same proportion as either China or Japan (16). Other statistics provide a similar picture (17-19).

So what caused the crisis? Clearly, the shadow banking system (mainly based around US and European financial institutions) succeeding in generating huge amounts of leverage and financing all by itself (24, 28). Banks can expand credit independently of their reserve requirements (30) – the central bank’s role is limited to setting short-term interest rates (30). European banks deliberately levered themselves up so they could take advantage of opportunities to use ABS in strategies (11), many of which were ultimately aimed at looting these same banks for the benefit of bank employees. These activities pushed long-term interest rates down. Short-term rates remained low because the Fed didn’t raise them as long as inflation didn’t appear to be an issue (25, 27).

The Asian countries played a small role as well. They didn’t want US/European-driven asset price inflation to spill over into distortions in their economies, and so they protected themselves by accumulating foreign exchange reserves (26 and 26 note). That was mean of them. If they had allowed more spillover, then the costs of the shadow banking system would have been partly borne by them, and that would have made the credit crisis less severe in the advanced countries (26).

Keep in mind that this is not a mere aesthetic argument. If you believe the Bernanke argument, you’ll argue that China needs to let the renminbi appreciate faster and provide more safety nets to its populace so they can shop almost as much as Americans do. If you accept the Borio/Disystat analysis, it means you need to regulate financial players and markets far more aggressively.

This VoxEU article by Hyun Song Shin provides further support for the Borio/Disytat thesis, as well as providing the additional benefit of providing a clear and simple explanation of some of the issues it raises.

By Hyun Song Shin, Professor of Economics at Princeton. Cross posted from VoxEU

It has become commonplace to assert that current-account imbalances were a key factor in stoking subprime lending in the US. This column says the ‘global banking glut’, i.e. the rise in cross-border lending, may have been more culpable for the crisis than the ‘global savings glut’. As the European banking crisis deepens, the deleveraging of the European global banks will have far-reaching implications not only for the Eurozone, but also for credit supply conditions in the US and capital flows to the emerging economies.

The ‘global savings glut’ is what Ben Bernanke called it. This phrase provided a powerful linguistic focal point for thinking about the surge in net external claims on the US on the part of emerging economies. The biggest worries concern the financial stability implications of these large and persistent current-account imbalances.

Since Bernanke’s 2005 speech (Bernanke 2005), it has become commonplace to assert that current-account imbalances were a key factor in stoking the permissive financial conditions that led to subprime lending in the US.

But maybe the finger is being pointed the wrong way. My recent research suggests that the ‘global banking glut’ may have been more culpable for the crisis than the ‘global savings glut’ (Shin 2011).

What is the ‘global banking glut’?

To introduce the distinction, it is instructive to start with the financial crisis in Europe. What role did current-account imbalances play there? There are some superficial parallels with the US in the run-up to the crisis.

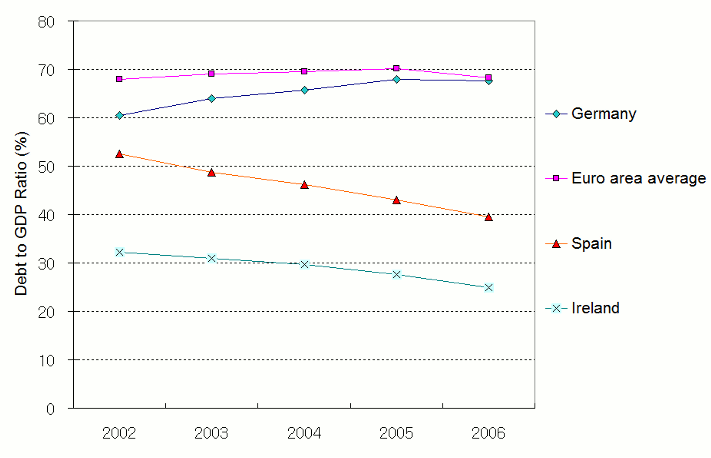

The current-account deficits of Ireland and Spain widened dramatically before the crisis (Figure 1). This despite the fact that Spain and Ireland were paragons of fiscal rectitude – with budget surpluses and low debt ratios (much lower than Germany’s and the Eurozone average in 2006, see Figure 2).

Figure 1. Current account of Ireland and Spain (% of GDP)

Figure 2. Government budget balance and debt-to-GDP ratios of Ireland, Spain and Germany

To push the analogy with the US further, imagine for a moment that the Eurozone is a self-contained miniature model of the global financial system. In this miniature model, Germany plays the role of China, while Spain and Ireland play the US.

According to the analogy, excess savings in Germany find their way to Spain and Ireland where they inflate the property bubbles there. The bubbles subsequently burst, resulting in the socialisation of private debt through bank bailouts and precipitating the sovereign-debt crisis.

However, the further we push the analogy, the stranger it gets. According to the ‘global savings glut’ hypothesis, Chinese savers favour US Treasuries because China lacks deep financial markets that could cater to demands for safe assets. In the miniature model of the savings glut for the Eurozone, Spanish and Irish bank deposits play the role of US Treasuries, since current-account imbalances in the Eurozone were financed through capital flows in the banking sector. To sustain the analogy, we would need to argue somehow that German savers shunned bank deposits in Germany to favour bank deposits in Ireland and Spain. Why would German savers believe that deposits in Spain and Ireland are safer than those in Germany? At this point, the savings glut analogy strains credulity and breaks down.

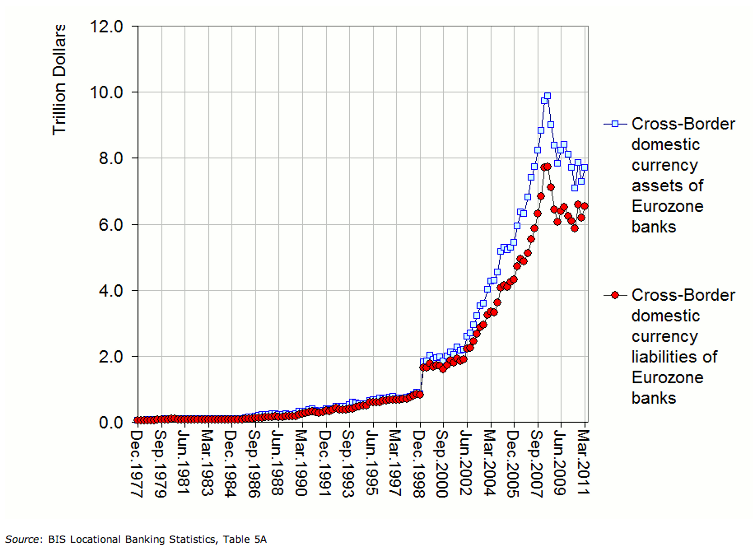

A more plausible narrative is a banking glut associated with the explosive growth of cross-border lending in Europe, as illustrated by Figure 3 which plots the cross-border domestic currency lending and borrowing by EZ banks.

Figure 3. Cross-border domestic currency assets and liabilities of EZ banks

There is a mechanical jump in the two series at the start of 1999 with the launch of the euro, as previously foreign-currency lending and borrowing are reclassified as being in domestic currency (i.e. euros). But from 2002, cross-border bank lending saw explosive growth as the property booms in Ireland and Spain took off and as European banks expanded their operations in central and Eastern Europe.

What drove European banks to do this? By eliminating currency mismatch on banks’ balance sheets, the introduction of the euro enabled banks to draw deposits from surplus countries in their headlong expansion. Meanwhile, the permissive bank-capital rules under Basel II removed any regulatory constraints that stood in the way of the rapid expansion. To be fair, the permissive bank risk-management practices epitomised by Basel II were already widely practised within Europe before the formal introduction, as banks became more adept at circumventing the spirit of the initial 1988 Basel Capital Accord.

Compared to other dimensions of economic integration within the Eurozone, cross-border mergers in the European banking sector remained the exception rather than the rule. Herein lies one of the paradoxes of Eurozone integration. The introduction of the euro meant that “money” (i.e. bank liabilities) was free-flowing across borders, but the asset side remained stubbornly local and immobile. As bubbles were local but money was fluid, the European banking system was vulnerable to massive runs once banks started deleveraging.

Europe’s crisis: A banking crisis first, a sovereign-debt crisis second

The banking glut hypothesis is a better perspective on the current European financial crisis than the savings glut hypothesis. The crisis in Europe is a banking crisis first, and a sovereign-debt crisis second. It carries all the hallmarks of a classic “twin crisis” that combines a banking crisis with an asset-market decline that amplifies banking distress. In the emerging-market twin crises of the 1990s, the banking crisis was intertwined with a currency crisis. In the European crisis of 2011, the twin crisis combines a banking crisis with a sovereign-debt crisis, where the mark-to-market amplification of financial distress worsens the banking crisis.

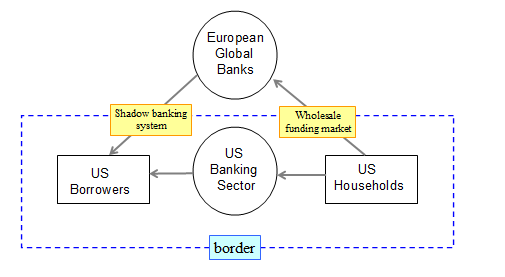

The banking glut in Europe was part of a global phenomenon, as documented in a recent paper delivered as this year’s Mundell-Fleming lecture at the IMF (Shin 2011). Effectively, European global banks sustained the “shadow banking system” in the US by drawing on dollar funding in the wholesale market to lend to US residents through the purchase of securitised claims on US borrowers, as depicted in Figure 4.

Figure 4. European banks in the US shadow banking system

Although European banks’ presence in the domestic US commercial banking sector is small, their impact on overall credit conditions looms much larger through the shadow banking system. The role of European global banks in determining US financial conditions highlights the importance of tracking gross capital flows in influencing credit conditions, as emphasised recently by Borio and Disyatat (2011). In Figure 4, the large gross flows driven by European banks net out, and are not reflected in the current account that tracks only the net flows.

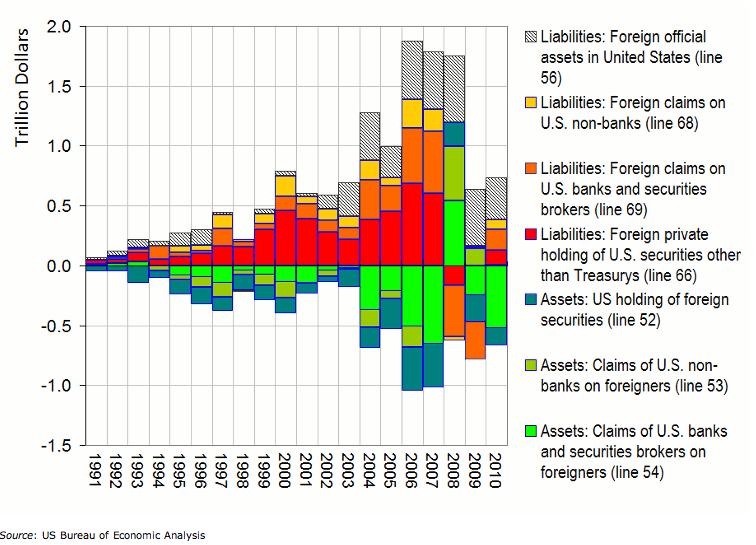

The netting of gross flows shows up in Figure 5, which plots US gross capital flows by category. While official gross flows from current-account surplus countries are large (grey bars), we see that private-sector gross flows are much larger.

Figure 5. Gross capital flows to/from the US

The downward-pointing bars before 2008 indicate large outflows of capital from the US through the banking sector, which then re-enter the US through the purchases of non-Treasury securities. The schematic in Figure 4 is useful to make sense of the gross flows. European banks’ US branches and subsidiaries drove the gross capital outflows through the banking sector by raising wholesale funding from US money-market funds and then shipping it to headquarters. Remember that foreign banks’ branches and subsidiaries in the US are treated as US banks in the balance of payments, as the balance-of-payments accounts are based on residence, not nationality.

European banks: Gross flows and US pre-crisis credit conditions

The gross capital flows into the US in the form of lending by European banks via the shadow banking system will have played a pivotal role in influencing credit conditions in the US in the run-up to the subprime crisis. However, since the Eurozone has a roughly balanced current account while the UK is actually a deficit country, their collective net capital flows vis-à-vis the US do not reflect the influence of their banks in setting overall credit conditions in the US.

The distinction between net and gross flows is a classic theme in international finance, but deserves renewed attention given the new patterns of international capital flows (see, e.g., Borio and Disyatat 2011). Focusing on the current account and the global savings glut obscures the role of gross capital flows and the global banking glut.

Net capital flows are of concern to policymakers, and rightly so. Persistent current-account imbalances hinder the rebalancing of global demand. Current-account imbalances also hold implications for the long-run sustainability of the net external asset position. For the US, however, the current account may be of limited use in gauging overall credit conditions. Rather than the global savings glut, a more plausible culprit for subprime lending in the US is the global banking glut.

As the European banking crisis deepens, the deleveraging of the European global banks will have far-reaching implications not only for the Eurozone, but also for credit supply conditions in the US and capital flows to the emerging economies. Just as the expansion stage of the global banking glut relaxed credit conditions in the US and elsewhere, its reversal will tighten US credit conditions. Its impact in the emerging economies (especially in emerging Europe) could be devastating. In this sense, there is a huge amount at stake in the successful resolution of the European crisis, not only for Europe but for the rest of the world.

No comments:

Post a Comment