This post from VoxEU is a good short form summary of how the Eurozone got into this fix. Its last para takes an unduly scolding tone that may turn off some readers, and does not reiterate the point made at the top, which is that the ECB needs to step up in a serious way to stem the crisis. Other remedies will take too long to implement and thus cannot change the trajectory under way.

By Charles Wyplosz, Professor of International Economics at the Graduate Institute, Geneva; Director of the International Centre for Money and Banking Studies. Cross posted from VoxEU

The EZ rescue strategy adopted in May 2010 failed to restore debt sustainability, avoid contagion, or reduce moral hazard. This column argues that a volte face is needed. The debt of Greece, Portugal and Italy – and perhaps Ireland, Spain and France as well – must be restructured to restore growth and end the crisis. All EZ nations should pay since their leaders’ decision to violate the Maastricht Treaty’s no-bail out clause is what brought us here.

Chancellor Angela Merkel has sent word that Germany cannot save the euro. She is right.

From the very start of the Eurozone crisis, it was clear that a domino game was under way and that a highly indebted German government should not be seen as the residual saviour. But keeping the euro will be costly and Germany will have to share the burden.

The solution will have to combine debt structuring and ECB lending in last resort to banks and governments. Angela Merkel needs now to lift the German veto.

All Eurozone leaders, including Mrs Merkel, are to blame for today’s predicament.

• The politically expedient decision of May 2010 – to bailout Greece but promise that it would be “unique and exceptional” – was officially sold as necessary to avoid contagion.

• Two years later, it is obvious that this has been a historical but predictable policy mistake (Wyplosz 2010).

The crisis has engulfed three small countries – Greece, Ireland and Portugal – and is now on its way towards Spain and Italy. France might well be next. These six countries’ public debts amount to 200% of German GDP. With its own debt of 80% of GDP, Germany cannot indeed stop the rot.

Moralistic rather than economic reasoning

The public debate in Germany and elsewhere is often moralistic, matching the economists’ concern with moral hazard.

• Countries that have long considered the government budget as a purely theoretical constraint cannot now simply ask for help.

• The same applies to countries that have allowed their banks to fuel a housing price bubble and now socialize the resulting private losses.

There is no case against the view that bad policies must have consequences. In this the moralisers are right.

But the issue is more complicated than meets the eye. We must ask:

• Which countries trampled the Eurozone’s fiscal discipline?

• What should be the consequences? and

• What are the costs for the monetary union as a whole?

Many ‘debt sinners’ in 2007

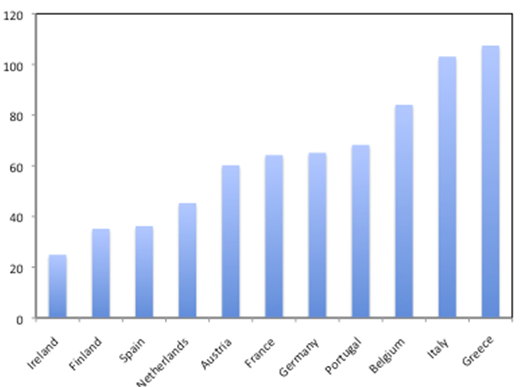

Right before the financial crisis of 2007-8, few Eurozone countries could claim to have been fiscally disciplined. The figure below shows that Finland, Spain and Ireland could, but not Greece and Italy. Most other Eurozone nations – including Germany – were in the grey zone. Then the wheels of fortune that drive self-fulfilling crises started to spin, leaving us with an impression that strong moral judgments have to be terribly relative.

Figure 1. Public debts in 2007 (% of GDP)

Source: AMECO, European Commission

Banking supervision laxity

As we know, poor bank supervision is what drove Ireland and Spain into the camp of guilty countries. Here again, the story is not over and several countries may soon be found guilty of forbearance.

• Top of the list are France and Germany.

• Had Greece not been rescued then some large French and German banks, already fragilised by the subprime crisis, could well have been ripe for costly bailouts.

The debt reduction scheme applied to Greece effectively provided these banks with an exit strategy, and was delayed long enough for them to dispose of a large part of their initial holdings of Greek public debt. Even so, these same banks remain on the danger list if more defaults are needed, which is in fact the case. The list of truly innocent countries includes a small number of small countries.

The consequences of bad debt and banking policy

As for consequences, the issue is incredibly difficult. Austerity has been the accepted norm for punishment.

Austerity proponents at first sought to characterise austerity as only moderately painful – and this a ‘good pain’ that would provide a useful lesson for future generations.

But the facts have now completely undermined this view.

• The myth of expansionary fiscal contractions, also known as the negative multipliers, has now been proven disastrously wrong.

• Its last proponents point to Latvia as proof that it works, but it unclear where this assessment comes from.

The Latvian public debt is still rising as a percentage of GDP and GDP is now 15% lower than in 2007 before the stabilization plan. True, this is up from a loss of 20% in 2010, but this merely illustrates how positive the multipliers are.

The costs to Latvia have been massive.

• Unemployment jumped to a rate 20% and still is at 16% and emigration has apparently been massive.

• Banks are foreign-owned and the owners decided to stay and absorb the losses.

• The only good news from Latvia is that the economic collapse only lasted three years, largely because wages have been quite flexible in this very small and very open economy, leading Blanchard (2012) to conclude that “the lessons are not easily exportable”.

Greece

The Greek experience is one of never-ending economic decline, massive unemployment and intense social hardship. Sure, the Greeks are being taught a lesson, but which one?

• Resistance to economic reforms is as intense now as it was before the crisis but xenophobia and the appeal of populist politicians is rising spectacularly.

• The multiplier debate tends to conceal the political consequences of austerity in the midst of a recession.

As economists, we also need to look slightly beyond our pond.

When these aspects are factored in, the consequences of the strategy adopted in 2010 are simply not justifiable, even on moral grounds. This is so especially as those who are punished most are not those that benefitted most from fiscal indiscipline in the run up to the EZ crisis.

The May 2010 strategy is a disaster: Admit mistakes and move on

The strategy adopted in May 2010 has not just failed to achieve its aims: restore debt sustainability, avoid contagion and reduce moral hazard. It has not produced a solution that is likely to bring the crisis to its end. A 180-degree turn is still needed.

Unfortunately it will be costly.

• A number of countries will never be able to achieve sustainable growth under the weight of their current public debts.

• This is the case of Greece, Portugal and Italy,

• The list may eventually widen to include Ireland, Spain and France.

Their governments will have to restructure their debts, totally in the case of Greece, partially – if done early enough – in the other cases.

• As the banks in these nations fail (because they did not adequately diversify their portfolios), bank bailouts will also have to be financed from outside.

Who will pay?

• Foreign banks will, of course, end up writing down the restructured sovereign debt; they, in turn, may have to be bailed out by their own governments.

• Official creditors too will suffer losses.

This includes the ECB, to the extent that it imposed insufficient haircuts in its various refinancing programs, and the shareholders of the EFSF and the ESM, which also happen to be the shareholders of the ECB.

Waiting only raises the eventual price

The more we wait, the deeper the economic deterioration – more lending to governments and more non-performing loans in banks – and the bigger the eventual costs.

• Importantly, the list of ‘bailer outs’ shrinks as the list of ‘bailed outs’ expands, so the costs of the rescue become concentrated on a decreasing number of healthy countries.

• Waiting too long implies that there is no healthy country left or no Eurozone any more, probably both.

The moral question reconsidered

Why should German and other taxpayers, mostly from the north, pay for the others, mostly from the south? Because their governments are responsible for the disastrous situation we are in.

• The rather well-crafted Maastricht Treaty had a no-bailout clause that was designed to protect all Eurozone taxpayers from fiscal indiscipline in other countries.

• Under Merkel’s leadership, this clause was first violated in May 2010, and then again to bail out Ireland, and again for Portugal and now for Spain.

This was an economic policy ‘crime’. It looked cheap at the time, at least under the assumption that there would be no contagion.

A basic moral principle is that criminals must be held responsible for the consequences of their acts, even if those acts are unintended. Eurozone taxpayers are the victims of their elected leaders. They now face the choice between breaking up the Eurozone and paying up. Paying up still is the cheaper alternative, but not for long.

No comments:

Post a Comment