A scheme proposed by a group called Mortgage Resolution Partners, which is being considered by San Bernardino, CA, to use the traditional power of eminent domain to condemn mortgages, was pretty certain to be a non-starter, so I’ve ignored it. But it’s gotten enough attention to have roused the ire of a whole host of financial services industry lobbying groups, as well as endorsements from Bob Shiller and Joe Nocera, and a thumb’s down from Felix Salmon, so it looked to be in need of serious analysis.

One of the big problems with this plan, which seems to have been overlooked so far, is that any municipality who goes down this path is likely to be the designated bagholder. Mind you, that isn’t based just on the general tendency of municipalities to be easy prey for clever bankers, but also based on the few, but nevertheless troubling, operational details that have been made public.

This is the theory of how the plan would work, from one of its prime promoters, law professor Robert Hockett:

Protecting the citizenry and heading off blight is what municipal eminent domain authority is for…And it is for them to do so in partnership with private investors who effectively render the Plan publicly costless – just as we’ve done since the earliest days of our republic in carrying out and financing local projects

If you believe that, I have a bridge I’d like to sell you.

No, this plan isn’t a “partnership”. There has been troubling little detail about what Mortgage Resolution Partners will do or how it will be paid. This whole process has been hidden from public view. Why wasn’t the original request for proposal made public? Why haven’t the operational arrangements, as in what the roles and obligations of the parties are, and most important, what the fees are, been reported anywhere?

The way this plan works is that MRP and its allies plan to steal. And no, I’m not exaggerating. But the odds are high that if this program were to go anywhere, it would be a costly and embarrassing disaster for its municipal backers.

MRP’s Fees Are Obscene

Individuals who’ve met with people involved in the MRP scheme have said, consistent with the very sketchy presentation on the MRP website, that it is acting only in an advisory capacity. Translation: it is not a partner, it’s a hired gun. And for that, it is to get a fee on every mortgage condemned, reportedly 5.5% (I assume of the value paid by the authority to the investors, but this is the sort of detail that needs to be made public). 5.5% is an egregious fee, particularly for a large scale, largely repetitive process where key tasks like servicing will be contracted out. My sources say MRP has a $6 million budget for PR (and that number suggests PR is defined rather liberally, and probably includes inducements like sports tickets). That give you an idea of how rich they expect the pickings to be. And it’s even more unreasonable when you look at the risks that will be borne by local governments detailed below (I’d be stunned if the authorities were shrewd enough to have MRP indemnify them against any of these hazards).

Municipality Bears Valuation Risk

The proposal has the municipal authority (the idea is that various localities will join one umbrella authority, presumably per state) borrowing funds from “investors” (key terms not specified) to condemn mortgages. MRP’s own website makes clear that they intend to target only performing mortgages. Yet various accounts also say consistently that MRP thinks it can condemn the mortgages at a discount to face value, and refi them at a profit. This premise is fundamental to the entire scheme working; it’s how the municipalities can afford to pay the considerable operational costs as well as MRP’s fees. And it amounts to theft.

One of the requirements of eminent domain is that the property owner be paid fair market value. For a performing mortgage, it’s awfully hard to argue that that is less than 100 cents on the dollar (in fact, as Felix Salmon points out, it’s actually more these days since interest rates have fallen). MRP argues that they ought to be less since 18% of homes that were performing but underwater in 2010 became delinquent in 2011 (aside, I wonder how many of these were people who defaulted because servicers told them they needed to be delinquent to qualify for HAMP). First, that figure should be lower for the remaining mortgages (presumably, the weakest borrowers default, so the ones who are left are presumably sounder). Second, that logic cannot extend to specific mortgages, since it is specific mortgages that are being condemned. Would you accept an offer less than the blue book value of your car simply because someone said you had a 5% odds of being in a car wreck in the next year? No, but this is the argument that is being made.

And the examples all presume large discounts. From Nick Timiraos of the Wall Street Journal:

For a home with an existing $300,000 mortgage that now has a market value of $150,000, Mortgage Resolution Partners might argue the loan is worth only $120,000. If a judge agreed, the program’s private financiers would fund the city’s seizure of the loan, paying the current loan investors that reduced amount. Then, they could offer to help the homeowner refinance into a new $145,000 30-year mortgage backed by the Federal Housing Administration, which has a program allowing borrowers to have as little as 2.25% in equity. That would leave $25,000 in profit, minus the origination costs, to be divided between the city, Mortgage Resolution Partners and its investors.

Now remember how this works: the municipality condemns the mortgages, then supposedly takes over the mortgage (more on that assumption soon). The loan would still have to be serviced but then would be refinanced, with FHA loans as the targeted takeout (properties would be pre-screened to fit FHA parameters) Institutional investors or banks would then loan the municipality the money to pay the prior owners of the mortgages the supposed fair market value for their condemned mortgages. So if things work out, the investors are providing a fairly short term bridge financing facility. If not, they’d presumably be repaid from ongoing cash flows from the mortgages. But how does that work? The last thing investors want is to be at risk of having a short term loan become a long term loan. Presumably, there are penalties of some sort if that happens. And what happens if borrowers who can’t refi default (if nothing else, shit does happen, a homeowner could die or suffer a job loss after the condemnation but before the takeout was in place). Given that the whole premise was to refinance the mortgages, would the municipalities be prepared to make new loans to replace the existing ones? I sincerely doubt the investors intend to provide longer-term financing. You’d need to see how various scenarios are dealt with and how risks and fees are shared to assess this plan. Yet these crucial details remain under wraps.

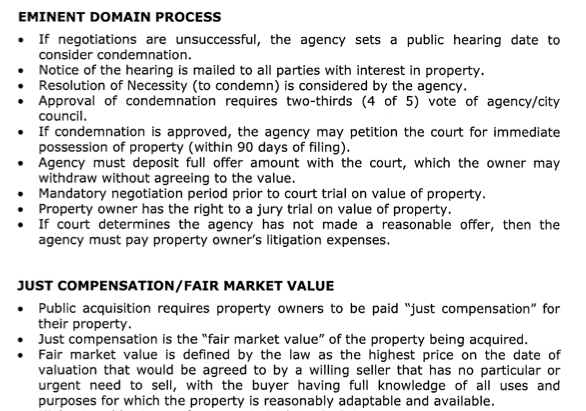

What happens if this all proves to be more costly than MPR promised? It’s certain that the municipality is on the hook, and it’s not hard to see how expenses could spiral out of control. Consider this layperson-friendly overview of the eminent domain process in California:

I’m not a lawyer, but it looks like it would be trivial to overturn the effort to buy performing mortgages out for less than par. First, whole loans are bought and sold, so it would not be hard to find comparables trading at vastly higher prices.

Second, the very act of condemning with an intended takeout at a higher price via a Federal government program smells an awful lot like a scheme to defraud. Clearly the ability to refi ad a much higher price than the condemnation price is proof in and of itself that the condemnation price was too low. And the best part? The party whose property is condemned can take the money offered and go fight in court for more. And if he wins, the other side, the municipality, pays his legal fees. Thee examples contemplate only $25,000 or say $50,000 of “spread” between the condemnation price and the refi amount. $25,000 doesn’t even get you started in litigation. Any level of lawsuits (particularly if the municipalities also have to repay the costs of big ticket lawyers on the other side) will run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars per borrower, pronto.

Municipalities/Special Authorities Would Be Targets of Suits on Constitutionality

This use of eminent domain is a huge stretch from its intended aims. It’s meant for public purposes, such as roads, new amenities, removal of blighted property, or redevelopment. You can see how disingenuous this approach is from the Robert Hockett paper attempting to justify its use. His evocation of the “public purpose” is to prevent foreclosures and neighborhood decay. But the program has nothing to do with that. It targets an only somewhat at risk population, and that capriciously. Fannie and Freddie borrowers (contra Felix) will not be eligible. Borrowers are also to be chosen to minimize the risk of litigation as well as on FHA eligibility, rather than based on some notion of need. For instance, my moles said that MRP was making sure no more than four loans would be condemned out of any one trust.

Given the unified outrage from the banking industry lobbyists (SIFMA, the ABA, the Financial Services Roundtable, the American Securitization Forum, the Mortgage Bankers Association, and the only bona fide investor, as opposed to sell side group, the American Mortgage Association), I’d expect a broad-based challenge on constitutionality, possibly in addition to a loan by loan war of attrition on pricing.

Now at first, you’d think that the big boys wouldn’t care. Aside from a few peeps by AMI, there were pretty much no complaints of the transfer from investors to banks embodied in the mortgage settlement. And no wonder. The banks are vastly more powerful than disenfranchised investors (who are in for the most part in the hands of institutional investors who don’t want to ruffle the banksters).

I had initially thought that the reason for the unified uproar was the ongoing top priority of not exposing the insolvency/impairment of the four biggest banks by making them write down their second liens to realistic levels. After all, one would think that condemning a first lien would force the wipeout of the second, right?

It turns out that may not be the case. Despite Hockett’s and others efforts to treat mortgages the same as real estate, they aren’t. Specifically, the reason the MRP scheme isn’t touching Fannie and Freddie mortgages apparently is that they are subject by Federal pre-emption from action by state authorities. Arguably, the same logic would apply to any second liens made by an OCC chartered bank. If the OCC said they were off limits, they’d be off limits (and notice, in keeping, the silence in all the public discussions about what would happen to the second liens). In addition, remember that FHA is the planned takeout, and FHA refis allow the seconds to stay in place as long as the lender agrees to resubordination. What lender wouldn’t be delighted to agree if the principal balance of the first lien gets reduced a ton? It makes his second a much better asset.

So if this program might help alleviate the second lien problem, why are the staunch defenders of Big Finance up in arms? Despite the huffing and puffing, it certainly doesn’t have anything to do with “no one will ever lend to you guys again.” The residential mortgage market is on government life support, and the incumbents have been completely unwilling to back reforms that might bring investors back into the pool.

The reason may be that if any mortgages that were condemned got a court ruling supporting a well below par value price, the ramifications would be considerable. Remember, these would be jury trials, and litigation is a crapshoot, even with the facts stacked in favor of investors, a few condemnations could still get a clean bill of health). A price that low is justified only if the court bought the idea that the mortgage was at imminent risk of default. The fact that these mortgages could be refied (and the investors were at risk of a takeout below that amount) would mean the servicers would be exposed to large scale litigation for their failure to do mods for similarly situated borrowers. The PSAs that limit mods either contain percentage restrictions, like 5% of the pool, or require that the borrower be in default or at imminent risk of default. Classifying a large new group of borrowers as being at imminent risk of default, and putting a discount on their mortgages would make it easy to arrive at pretty large damages.

What Happens If/When Servicers Can’t Produce Properly Endorsed Notes? The promoters are blithely assuming servicers can produce properly endorsed notes and assign liens. Has anyone done an analysis of the issues here? Recall, as a particularly prominent example that in Ibanez, two different servicers had two years to produce evidence of ownership. As noted in the concurring opinion:

The plantiff banks….have simply failed to prove that the underlying assignments of mortgages that they allege (and would have) entitled them to foreclose ever existed in legally cognizable form before they exercised the power of sale that accompanies those assignments.

Lack of Transparency Many elements of how this scheme came about are troubling. While the interested municipalities have released the agreement that creates the joint authority, that tells us pretty much nada about the money and risk issues.

This program looks to have been awarded to MRP with insufficient competition. Was there a request for proposal? If so, why has no one seen it? This process smacks of special dealing (for instance, designing a process to favor MRP, say by drafting the RFP to assure they’d be selected, or having too narrow a window for proposals to allow other firms to come forward). The RFP, the proposed agreement, any correspondence, and a record of meeting between public officials and MRP should be made public. Par for the course, San Bernardino announced only today that a public meeting on this issue will be held Friday. And this also comes as the municipality is considering filing bankruptcy. This is the worst possible time for it to be saddling up for more risk, yet desperation seems to have badly clouded their officials’ judgment.

If you are in the San Bernardino area, the meeting notice claims “all writings received by the Board of Directors related to these items are public records” and will be available for review. I hope an NC reader can go and see if the RFP and contract are indeed being made public. If so, it would be very helpful to provide a summary of them for the benefit of the public; we’d be delighted to publish it. And if they aren’t, it would be hard not to surmise that the officials are pulling a fast one.

No comments:

Post a Comment