By Delusional Economics, who is horrified at the state of economic commentary in Australia and is determined to cleanse the daily flow of vested interests propaganda to produce a balanced counterpoint. Cross posted from MacroBusiness

I mentioned back in early July that Spain had a serious political problem brewing because the draft Memorandum of Understanding for the Spanish banking system clearly stated that:

Banks and their shareholders will take losses before State aid measures are granted and ensure loss absorption of equity and hybrid capital instruments to the full extent possible.

From a market perspective this is absolutely the correct thing to do. Equity is a risky business. You take a punt, the banks falls over, your money it gone, fair enough. But in Spain it’s not that simple because of something I commented on in April:

The key in a banking crisis is to keep the confidence of depositors. But while many countries relied on capital injections and government guarantees, Spanish banks have added a unique twist of effectively turning some depositors into equity holders. That puts customers on the front line.

Some banks started by persuading depositors to switch from low, interest-bearing accounts into preference shares, which paid a fixed, higher interest rate. The benefit for the banks was that these securities counted as core capital under banking rules. UBS says Spanish banks issued €32 billion ($42.7 billion) of such instruments from 2007 to 2010.

But as the crisis deepened, these instruments became illiquid, trading at deep discounts. At the same time, they ceased to count as core capital under new rules known as Basel III. So banks have encouraged investors to convert preference shares into either common stock or mandatory convertible notes, which pay a high initial yield before later converting into stock.

And so now, under the watchful eye of the Spanish regulators, depositors in Spanish banks had been converted into equity holders and these same people were about to see their savings eaten up by the first stages of a banking bailout.

Although there are other factors involved, I think this is one of the primary reasons Mariano Rajoy has been so hesitant to move forward with any bailout, and it comes as no surprise that he is now attempting to negotiate a way out for these people:

The Spanish government is in talks with Brussels to allow tens of thousands of retail clients who bought risky savings products from now nationalized lenders to avoid losing their investments as part of Spain’s bank bailout.

In place of inflicting large losses on small savers who purchased savings products linked to preference shares in in the lenders known as cajas, the Spanish government is negotiating a compromise where they will suffer an instant haircut, and then be repaid in full over time by their banks, people familiar with the talks said.

The decision to inflict losses on holders of high interest preference shares and subordinated debt in rescued savings banks has been highly controversial in Spain, with the terms of the country’s bank rescue not distinguishing between professional and retail investors.

Apart from the obvious question of whether they will actually get a deal, the other question is will the banks be in any position to make those payments in the future. As WSJ reports, the banking system looks increasingly flakey as deposits continue to leave the country and the hole is filled by ECB:

Spanish banks borrowed a record amount from the European Central Bank in July, as other sources of funding evaporated further in the weeks following the announcement of a €100 billion ($123 billion) bailout for the country’s financial industry.

Bank of Spain data indicated that net ECB borrowing rose to €375.55 billion from €337.21 billion in June. It was the 10th straight month of increases, highlighting how the country’s lenders are having more and more difficulty financing themselves through private investors.

Spain’s traditional funding sources have been dwindling as the economy sinks deeper into a downturn. During the Spanish construction boom of the past decade, German and other European banks were more than willing to fund the rapid expansion of the Spanish banking system, inflating the country’s credit bubble.

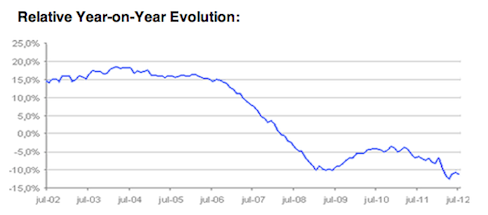

And the latest report from Tinsa makes it very clear that the bubble’s deflation is far from over:

The IMIE General index registered a year-on-year decline of 11.2% in July, pushing the index down to 1577 points. The cumulative decline in house prices since the market peaked in December 2007 is 31%.

In terms of the cumulative decline in house prices by region since peak prices, there was a 37.2% fall in July for the “Mediterranean Coast”; followed by 33.5% for “Capitals and Major Cities”, 32.1% for “Metropolitan Areas”, 29.2% for the “Balearic and Canary Islands” and 25.9% for “Other Municipalities”, which comprises the remainder.

Mariano Rajoy is expected to meet Herman Van Rompuy, Angela Merkel, Mario Monti and Finland’s President, Sauli Niinistoe, over the next few weeks in order to discuss his country’s future. It is, however, increasingly obvious that he will have little choice to accept whatever he is given, and I have to question again exactly how long he has left in politics.

No comments:

Post a Comment