Two major government settlements later, this position is looking awfully strained. And the Fed, in stonewalling Elizabeth Warren’s and Elijah Cumming’s efforts to get more information about the Independent Foreclosure Reviews, presented the bad practices as servicer policies, which means that they were deliberate, hence, fraudulent.

By way of background: Warren and Cummings have been asking the OCC and Fed for some time for more information about what happened in the foreclosure reviews. Out of fourteen information requests they made in a January letter, they got only one question answered in full, and mere partial responses to three other questions. They requested, and got, a meeting yesterday. They issued a letter Wednesday that described what transpired. Key sections:

Two years ago this week, your offices issued a public report announcing that you determined that 14 mortgage servicing companies were engaging in “violations of applicable federal and state law.” You found that these abuses have “widespread consequences for the national housing market and borrowers.” You also explicitly referenced instances of abuse, including illegal foreclosures against our nation’s men and women in uniform who are protected by the Servicemembers Civil Relief Act (SCRA)….

We have requested information about the process used to conduct this review and the extent to which violations of law were found….

At the meeting yesterday, Federal Reserve staff argued that the documents relating to widespread legal violations are the “trade secrets” of mortgage servicing companies. In addition, staff from the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OCC) argued that these documents should be withheld from Members of Congress because producing them could be interpreted as a waiver of their authority to prevent disclosure to the public of confidential supervisory bank examination information.Now since the Fed is apparently making this absurd argument in all seriousness, let’s look at the implications. A trade secret is a form of intellectual property. I encourage IP experts to pipe up in comments, but my understanding, based on the experience of a client who successfully sued a former employee for violating trade secrets, is that it is difficult to prove that your internal know-how rises to the level of being a trade secret. One of the key elements in making the case is that you have to show you went to some length to keep your special tricks secret, such as limiting access to them, having employees sign confidentiality agreements, etc.

Why does this matter? You can’t have internal knowledge rise to the level of being a trade secret unless their was an institutional decision to keep it secret. That means the Fed is effectively saying that servicer management, and almost certainly bank management (since servicing units don’t have their own corporate counsel) was fully aware of the nature of the practices at issue and chose to keep them secret, supposedly for competitive reasons. This is fact is one of the things lawyers have been eager to establish, namely that bank management knew full well all these servicing tricks were happening, and sought to protect them as important sources of profit. Way to go, Fed!

Now, of course, this argument is revealing in a lot of other ways. The Fed has also just admitted it thinks it is more important to protect bank knowledge of how to break the law than expose the information. So the Fed has also made explicit that it wants to preserve banks’ ability to rip off people. So the Fed’s official policy is bank profits trump the law. Not that we didn’t know that, but it has now been stated in a baldfaced manner.

The OCC’s position, that they need to preserve confidential bank examination information, is equally ridiculous (the letter gives a long-form debunking). Warren and Cummings noted,

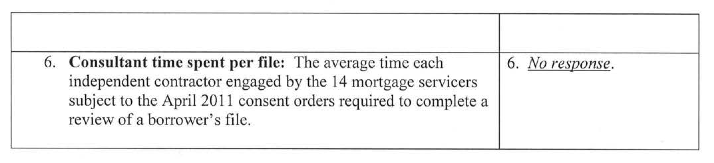

You may protect against such a waiver by including standard language in a cover letter explaining that providing documents to Members of Congress, even if normally not disclosed to the public because of their proprietary or confidential nature, does not constitute a waiver.But it’s doubtful that the information at hand is “bank examination information”. The reason for keeping bank examination results confidential is to prevent bank runs. Mortgage servicing units are not banks. In fact, the OCC said repeatedly when it was pilloried for its failure to supervise servciers that didn’t have much in the way of formal authority over them. It wasn’t acting as a bank examiner of servicing units for the period that was the focus of the IFR, 2009 and 2010. Given the poor control over information during the IFR (for instance, at Bank of America, the army of temps who performed the project didn’t sign enforceable confidentiality agreements), and the fact that lots of relevant information (investor reports, court documents, including the affidavits used for the fraudulent fees) are public records, the OCC argument isn’t credible. It becomes even more of a howler when you look at the questions that the OCC and Fed are refusing to answer. Tell me how bank operations might be harmed by answering this question, for instance:

And why are the Fed and the OCC fighting Warren and Cummings so hard? It’s not as if the information they seek would help an individual borrower in litigation against a bank, except in a very general way. For instance, Warren and Cummings ask for the number of borrower files in which unsafe or unsound practices were found. If it was revealed that Bank of America had a high proportion of files with errors, as our whistleblowers found, that might persuade a judge that a borrower case not be thrown out in summary judgment.

But the real exposure of the banks is to investor litigation. The Bank of America sources who did fee reviews found virtually all their files had errors (their reflex was to say all files had errors, but most would then correct themselves and say 90% or 95% since they could not be sure someone didn’t get a batch of files that were fine). In many cases, the errors weren’t large enough to have caused a borrower to lose his house. But remember, if a home is foreclosed on, all fees (late fees, attorney fees, property inspection charges) are reimbursed first, so excessive frequency or size of foreclosure-related fees is a transfer from investors to servicers. So if the OCC and Fed were to confirm that there were large-scale abuses, investors might saddle up to go after the servicers.

This exchange also confirms something the public knows all too well: the regulators are in the business of protecting the banks, and only secondarily in enforcing the law. And until that changes, it is the safety and soundness of the population that is at risk.

Source

No comments:

Post a Comment